A new near-Earth asteroid is detected on January 10, 2023 by an international team using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) mounted on the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, a program funded by the National Science Foundation. The team was searching in the twilight region of the sky, looking for asteroids hiding in the inner Solar System, near to and within the orbit of the Earth.

A week later the new discovery is announced by the Minor Planet Center (MPC), and the asteroid is assigned the designation “2023 PDC”. (To reinforce the fact that this is not a real asteroid, we are using three letters in the designation, something that would never be done for an actual asteroid.)

The MPC’s initial assessment reveals that the new asteroid’s orbit approaches the Earth’s orbit very closely, within 7.5 million kilometers (4.6 million miles), and that the asteroid is probably at least several hundreds of meters in size. Together, these two properties imply that 2023 PDC is a Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (PHA).

JPL’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) computes an estimate of 2023 PDC’s orbit that is as accurate as possible, but since there is only a week of tracking and the asteroid is very distant (roughly 200 million kilometers or 120 million miles from Earth), that orbit estimate is still very uncertain. CNEOS confirms that 2023 PDC’s orbit does indeed approach very close to Earth’s, but the asteroid itself will not approach close to Earth for many years.

CNEOS’s Sentry impact monitoring system determines that 2023 PDC has a 1-in-ten-thousand chance of impacting Earth in the year 2036. A similar conclusion is reached by ESA’s Near-Earth Objects Coordination Centre using their Aegis impact monitoring system.

On the Palermo Scale 2023 PDC rates -0.88, high enough to place it at the top of the Sentry Risk list. On the Torino Scale the asteroid is rated 1 (Green).

Little is known about 2023 PDC’s physical properties other than its approximate size, which is inferred from its brightness. It currently has a very faint visual magnitude of 21.7, but that faintness is a result of its great distance. The asteroid’s absolute (intrinsic) magnitude is estimated to be H = 19.4 +/- 0.3, which indicates that that it is quite large, and could be several kilometers in size, depending on its albedo (reflectivity). Allowing for the full range of possible albedos, the size of 2023 PDC is most likely in the range 220 - 660 meters (720 - 2160 feet), with a median size of 470 m (1540 ft). However, there is a very small chance that 2023 PDC is even larger, possibly as large as 2 km (1.26 miles).

2023 PDC’s orbit about the Sun is “Earth-like” in the sense that it is fairly circular, its distance from the Sun is similar to Earth’s and its orbital plane is only moderately inclined to that of the Earth. The asteroid is 0.90 au from the Sun at its closest point and 1.07 au at its farthest. (Here, “au” denotes “astronomical unit”, the mean Earth-Sun distance of 149,597,870.7 km or 92,955,807 miles.)

The asteroid’s orbital period about the Sun is 359 days, very similar to Earth’s 365 days. As a result, 2023 PDC moves quite slowly relative to our planet, on average, as both bodies orbit the Sun.

As the tracking dataset has grown, the orbit of 2023 PDC has become more certain, and the chance of impact in 2036 has grown. Now, on April 3, 2023, after over two months of tracking, the impact probability is estimated to be about 1%. If the asteroid is on a collision course, the date of the impact can be predicted accurately: October 22, 2036.

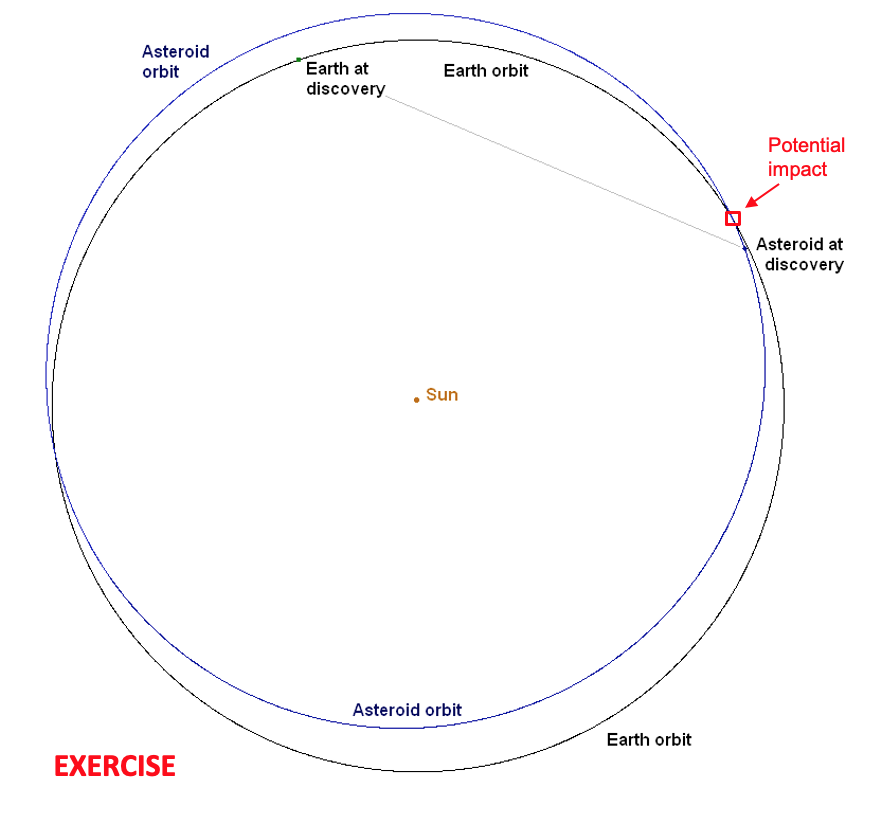

The following diagram shows the orbits of 2023 PDC and Earth along with their positions at the time the asteroid was discovered on January 10, 2023. The point at which the orbits intersect, and where an impact is possible, is highlighted by a red square. The orbit of 2023 PDC is clearly very similar to Earth’s: as it orbits the Sun, the asteroid spends about equal time inside Earth’s orbit as it does outside. This diagram projects the asteroid orbit into the plane of the Earth’s orbit; it does not show that in three dimensions, the asteroid’s orbit is inclined by about 10 degrees; most of the asteroid’s orbit inside of Earth’s is above the plane of this diagram, while most of the portion outside Earth’s orbit is below the plane of the diagram.

|

| Orbit of asteroid 2023 PDC |

As is evident from the diagram, 2023 PDC is currently very distant from Earth (1.33 au, or 200 million kilometers), far too distant for a radar detection. But astronomers continue to track it almost every night using large optical telescopes. These are challenging observations because the asteroid is located near the twilight region of the sky. There is only a short window of time after sunset when the sky gets dark enough and the asteroid is still far enough above the horizon to be detected.

As the diagram shows, 2023 PDC is currently about 85 degrees “behind” the Earth as both bodies orbit the Sun in a counter-clockwise direction at similar speeds. As a result of its slightly shorter orbital period, the asteroid will gradually catch up to our planet until it approaches very close in 2036. That close approach could result in an impact, if the moment the asteroid laps our planet happens to occur at the highlighted orbital intersection point.

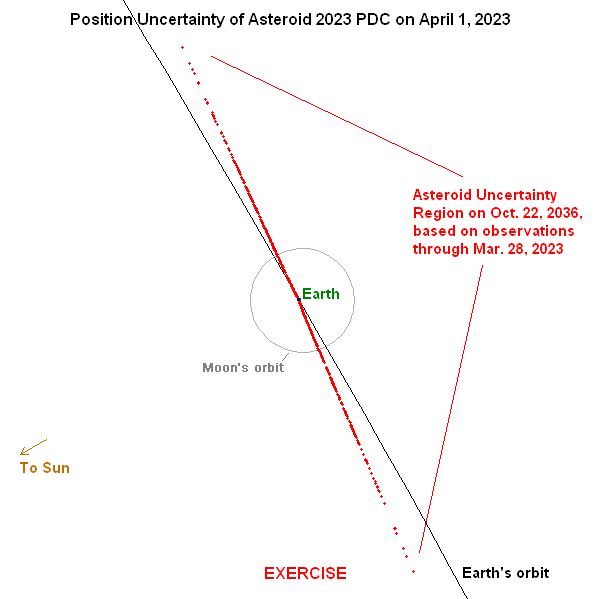

The following diagram zooms in on the intersection point of the orbits of 2023 PDC and the Earth, and shows the current uncertainty in the predicted position of the asteroid when the Earth crosses through the intersection point on October 22, 2036. The uncertainty region is traced out by random-sample cases whose positions are shown as red dots. The region extends to several lunar distances on either side of Earth.

|

| Current uncertainty in predicted position of asteroid 2023 PDC on October 22, 2036 |

As 2023 PDC is observed over subsequent months and years, its orbit will become better determined and the predicted uncertainty region for 2036 will shrink in size. If the Earth remains in the region as it shrinks, the impact probability will increase; if the Earth falls outside the region as it shrinks, the impact probability will go to zero.

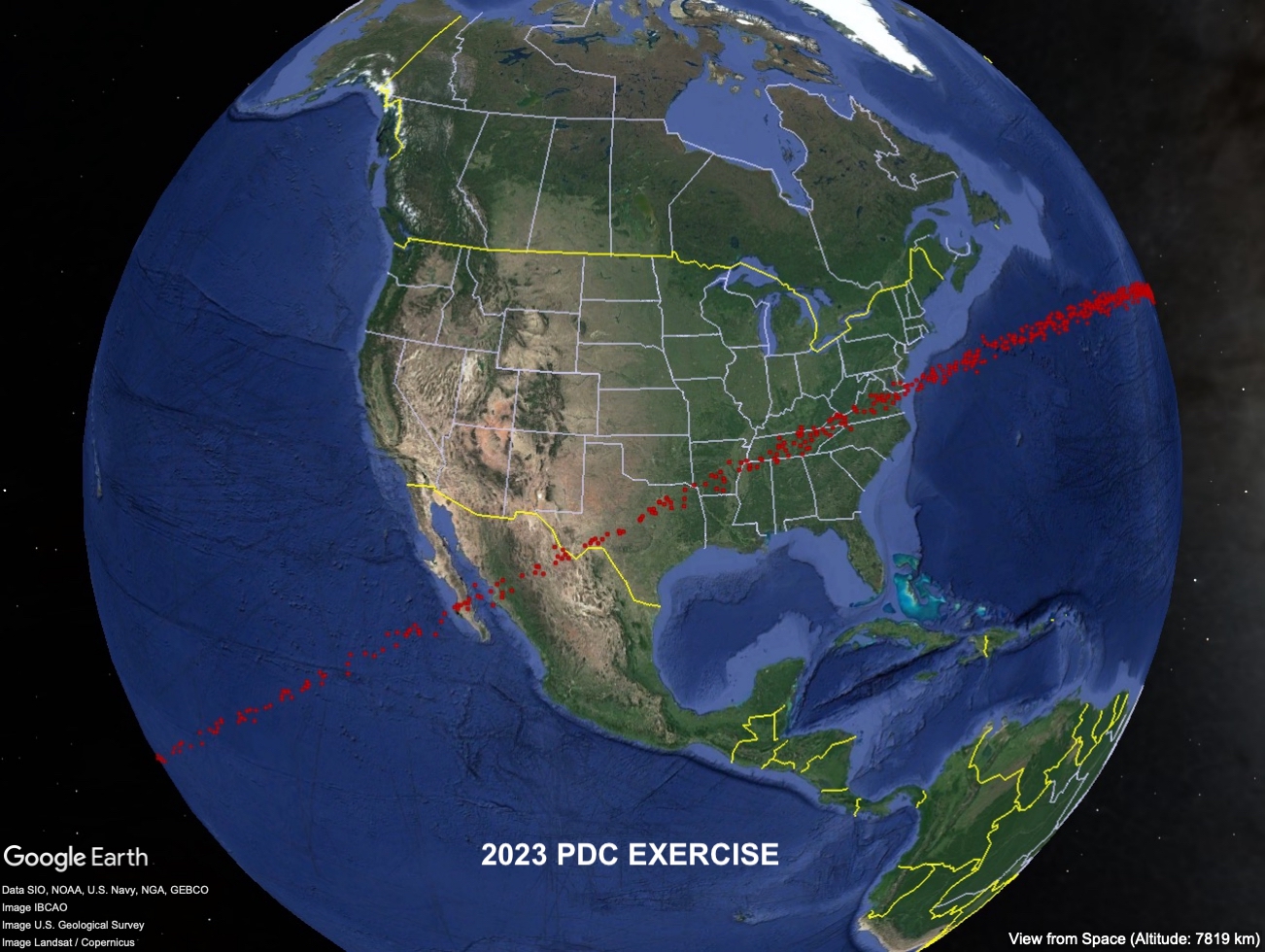

2023 PDC’s uncertainty region at the time of the potential impact is hundreds of times longer than the diameter of the Earth, but its width is only a few hundred kilometers. When the Earth crosses the asteroid orbit in 2036 and sweeps through the uncertainty region, the intersection creates a so-called “risk corridor” across the surface of the Earth. The risk corridor traces the region where the asteroid might impact; it cannot impact outside this region. The corridor wraps more than halfway around the globe, spanning from the South Pacific Ocean on the western end, across the U.S. and Atlantic Ocean, western, central and southern Africa, and all the way to the southern Indian Ocean at the eastern end. The red dots on the following two Google Earth images show some of the possible impact points. This diagram was produced by filling the uncertainty region in space with thousands of random-sample cases and computing where those cases would impact when the Earth sweeps through the region.

|

| Risk corridor for 2023 PDC - Western portion |

|

| Risk corridor for 2023 PDC - Eastern portion |

A Google Earth kml file for these impact points is available here.

A table of the impact circumstances of potential impact points along the central axis of this corridor can be found here. The columns of this table are as follows:

xi & zeta are the Opik b-plane coordinates of the trajectory, in km

Lat & ELon are the latitude and East longitude of the impact point, in degrees

Vel is the impact velocity in km/s

Az & El are the azimuth (measured eastwards from North) and elevation of the incoming velocity vector, in degrees

Time is the UTC time of the impact on the impact date, 2036-Oct-22.

The red dots tracing the risk corridor are randomly distributed within the region. While there are gaps between the points shown here, the risk corridor is in fact a continuous region, with the impact probability proportional to the average areal density of the points. The points become more widely spaced towards the end of the corridor because the asteroid enters at shallower elevation angles in those regions.

Impact probability is estimated from the available astrometric (sky-position) observations, and it depends most critically on the length of time over which an asteroid has been observed. 2023 PDC has been tracked for only a couple months, yielding only a few dozen observations. Tracking should continue for a couple more months, but must then cease for several months because the asteroid will move even farther into the daytime sky and will be lost in the glare of the Sun. Tracking observations should resume late in 2023 as the asteroid moves back into a darker sky, and when that happens the impact probability will change dramatically. If the asteroid really is on an impact trajectory, that should be known with certainty by late 2023. Conversely, if the asteroid is not on an impact trajectory, the impact probability should drop to zero by the end of 2023.

Beyond 2023 the asteroid should remain almost continuously observable as it slowly approaches our planet. It will stop dipping into the twilight sky in its yearly loops, will brighten and become generally easier to observe.

As the observation dataset grows, the orbit of 2023 PDC will become increasingly well determined, and if the asteroid is on an impact trajectory, the predicted impact region will become increasingly certain.

A special version of the JPL orbit viewer has been created for this object and can be accessed here.

A Google Earth kmz map file showing the damage swaths and example damage footprints at Epoch 1 is available here.

The orbit for a “worst case” trajectory for 2023 PDC has been loaded into JPL’s HORIZONS system, and can be accessed via the name “2023 PDC” or “PDC23”. This trajectory is not necessarily the current best estimate for 2023 PDC, which will change from day to day as observations are added, but rather the trajectory within the uncertainty region that passes closest to the geocenter on Oct. 22, 2036 (in other words, the trajectory that impacts closest to the center of the b-plane). HORIZONS can be accessed with this object preloaded via this web-interface here.

For those who wish to use SPICE Toolkit software to examine the trajectory of 2023 PDC, an SPK file for this same “worst-case” orbit has been created and is available here:

https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/ftp/xfr/2023-PDC/2023_PDC-s3-merged-DE441.bsp

The SPK file is consistent with and contains additional DE441 planetary ephemeris information over the time-span 1998-Jan-01 through impact on 2036-Oct-22, permitting retrieval of object state vectors at any arbitrary instant within that timespan.

The orbit for the “worst case” trajectory for 2023 PDC, described above, has been loaded into the JPL/Aerospace Corp. NEO Deflection App. This on-line tool allows users to study the velocity change (delta-v) required to deflect the 2023 PDC trajectory away from the Earth, as a function of deflection time. Specific amounts of impulsive velocity change can be applied at specific times before impact and the resulting deflection in the impact b-plane is shown. The App can also be configured to calculate kinetic impactor spacecraft trajectories, as well as the spacecraft masses that can be launched onto those trajectories by various launch vehicles. The App calculates the delta-v applied to the asteroid when one or more kinetic impactors hit it, as a function of asteroid size, density and momentum enhancement factor beta, and determines the Opik b-plane coordinates, xi and zeta, of the deflected trajectory during the 2036 encounter. Using these coordinates, you can roughly determine the impact point of the deflected trajectory by interpolating in the table of impact circumstances given above. A complete description of the app is available here.

The 2019 PDC trajectory is also loaded into the App along with trajectories of many other simulated Earth impactors.