There are a number of NASA supported Near-Earth Object (NEO) discovery teams currently in operation. The early efforts to discover NEOs relied upon the comparison of photographic films of the same region of the sky taken several minutes apart. The vast majority of the objects recorded upon these films were stars and galaxies and their images were located in the same relative position on these films. Early discovery techniques included blink comparators and stereomicroscopes to examine the photographic images. Because a moving NEO would be in a slightly different position on each photograph and the background starts and galaxies were not, the NEOs appeared to jump back and forth when each image, in turn, was quickly viewed through a so-called blink comparator. Alternately, the NEO’s image appeared to “rise” above the background stars when two different and slightly offset images were viewed with a special stereo viewing microscope.

All of the NEO discovery teams currently use so-called charged couple devices (CCDs) rather than photographic images. These CCD cameras are similar in design to those used in cell phones and they record images digitally in many electronic picture elements (pixels). The length and width of a CCD detector is usually given in terms of pixel elements. A fairly common astronomical CCD detector might have dimensions of about 2000 x 2000 pixels. While the CCD technology allows today’s detectors to be more sensitive and accurate that the older photographic images, the modern discovery technique itself is rather similar. Separated by several minutes, three or more CCD images are taken of the same region of the sky. These images are then compared to see if any NEOs have systematically moved to different positions from one image to the next. For a newly discovered NEO, the separation of the object’s location from one image to the next, the direction it appears to be traveling and its brightness are helpful in identifying how close the object was to the Earth, its size and general orbital characteristics. For example, an object that appears to be moving very rapidly from one image to the next is almost certainly very close to the Earth. Sophisticated computer-aided analyses of the CCD images have replaced the older, manual detection techniques but often times, a new NEO discovery is still verified using the human eye.

Not surprisingly, discovery teams who search the largest amount of sky each month will have the most success in finding new NEOs. How much sky each telescope covers per month will depend upon a number of factors including the number of clear nights available for observing, the sensitivity and efficiency of the CCD detector and the field of view of the telescope. It is also important for search teams to extend their searches to greater and greater distances from the Earth or, in other words, go to fainter limiting magnitudes. A 6th magnitude star is roughly the limit of a naked eye object seen under ideal conditions by someone with very good eyesight. A 7th magnitude star would be 2.5 times fainter than a 6th magnitude star and an 8th magnitude star would be 6 times fainter than a 6th magnitude object (2.5 x 2.5 = 6.25). A difference of 5 magnitudes is a brightness difference of nearly 100 (2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 is equal to about 100).

In 1998, NASA established a goal to discover 90% of the NEOs larger than one kilometer in diameter and in 2005, Congress extended that goal to include 90% of the NEOs larger than 140 meters. There are thought to be about 1000 NEAs larger than one kilometer and roughly 15,000 larger than 140 meters. The progress toward meeting these goals can be monitored on the NEO Discovery page.

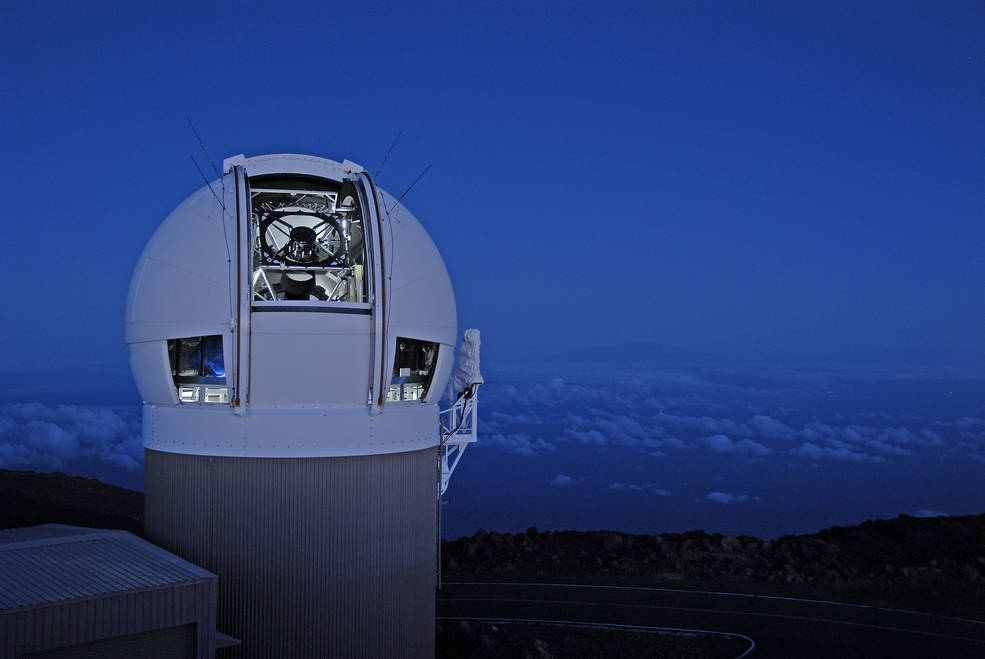

Since NASA’s initiation of the NEO Observations program in 1998, Near-Earth Object (NEO) surveys have been extremely successful finding more than 90% of the Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs) larger than one kilometer and a good fraction of the NEOs larger than 140 meters. The vast majority of NEO discoveries have been due to NASA-supported ground-based telescopic surveys including the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) and Spacewatch near Tucson Arizona, the LINEAR project near Socorro New Mexico, Pans-STARRS1 on Haleakala, Maui, Hawaii, LONEOS near Flagstaff Arizona and the NEAT project run by NASA/JPL. Using a near-infrared space telescope in an Earth polar orbit, the NEOWISE project was actively discovering and characterizing NEOs for ten months in 2010 before its cryogens were exhausted. It continued another four months into early 2011 as a post-cryogenic mission. The LONEOS and NEAT surveys have been discontinued and Spacewatch is now primarily a follow-up facility.