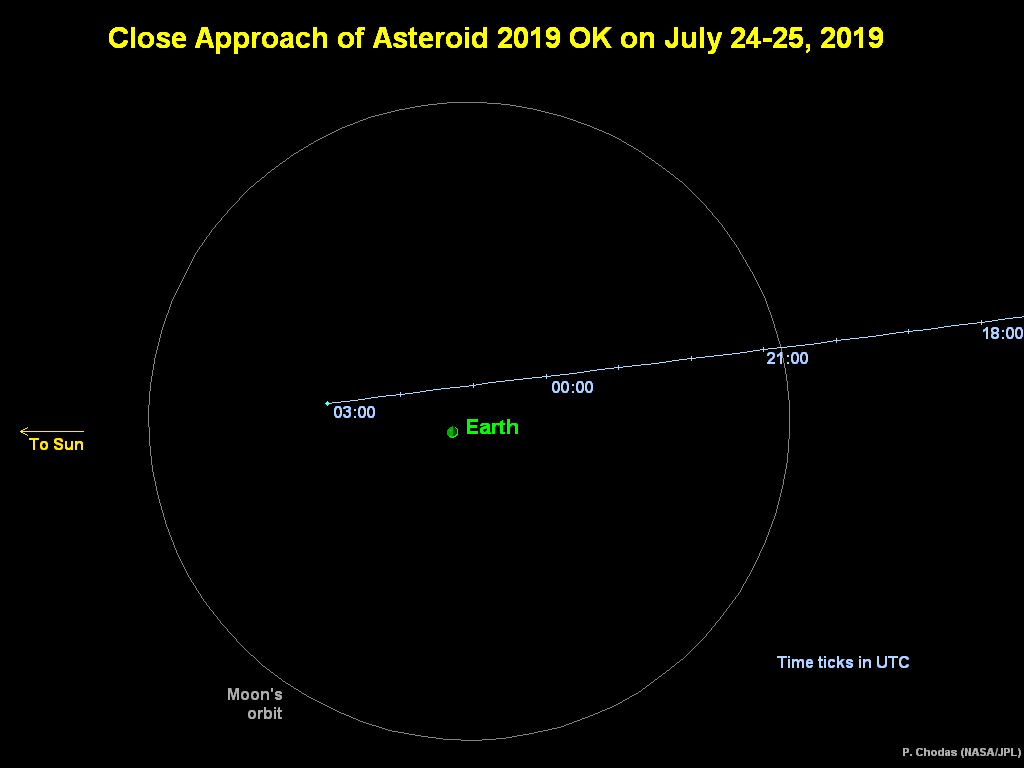

On the evening of Thursday, July 24, a football-field-sized asteroid passed close to the Earth with very little warning. The asteroid, designated 2019 OK, approached Earth at about 40,400 miles (65,000 kilometers) above the surface, one fifth the distance to the Moon. Other known asteroids have passed by closer, and a few very small asteroids have even impacted our atmosphere just after discovery, but none have been as large: 2019 OK is estimated to be 195-425 feet (60-130 meters) in size. The asteroid was first reported earlier that same day by the Southern Observatory for Near-Earth Asteroids Research (SONEAR) in the State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The orbit of asteroid 2019 OK is now well understood. This most recent flyby is the closest that the asteroid will come to Earth for at least the next 200 years.

While close-approaching asteroids much smaller than 2019 OK have been discovered earlier and further away from Earth, several factors contributed to the lateness of this asteroid’s detection.

The orbit of asteroid 2019 OK is highly elliptical, carrying it from within the orbit of Venus to well beyond Mars’ orbit. The time it spends near Earth and is detectable by current telescope capabilities is relatively short. Also, astronomers hunting near-Earth objects (NEOs) must look for a telltale movement against the background of stars in the sky to discover NEOs and track their orbits (see How a Speck of Light Becomes an Asteroid). Without enough movement, current ground-based asteroid surveys have difficulty identifying that a particular point of light is an asteroid instead of another star. As 2019 OK approached Earth, the alignment of its orbit relative to Earth’s positon caused it to appear not to move much relative to the stars in the sky until the last few days, finally revealing itself.

“An asteroid of this size coming this close to Earth is a pretty rare event – on the order of about twice a century,” said Paul Chodas, manager of NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at JPL. “And an impact by an asteroid of this size is rarer still, on average only on the order of once every several thousand years.”

If 2019 OK had entered and disrupted in Earth’s atmosphere over land, the blast wave could have created localized devastation to an area roughly 50 miles across. If the asteroid had entered over the ocean, it would have been a bad day for any sailing vessels in the vicinity, but the sea would have absorbed the great majority of the impact’s energy and it is doubtful that a tsunami would have been created.

“It is interesting to note that if a space-based infrared telescope had been on station and scanning the skies two years ago, it probably would have detected 2019 OK back then and this year’s close encounter would not have been a surprise,” said Chodas. “That shows the potential of a space-based asteroid survey.”

JPL hosts the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies for NASA’s Near-Earth Object Observations Program, an element of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office within the agency’s Science Mission Directorate.

More information about asteroids and near-Earth objects can be found at:

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/asteroidwatch

For more information about NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/planetarydefense

For asteroid and comet news and updates, follow AsteroidWatch on Twitter: https://twitter.com/AsteroidWatch

DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA

818-354-9011

agle@jpl.nasa.gov